Eramet’s adoption of GIS at the enterprise scale helps it meet its commitments to stakeholders from local communities, national agencies, nongovernmental organizations, and shareholders.

In Senegal, one of the world’s largest titanium and zirconium mines is always on the move. The French mining company Eramet, which operates the mineral sands extraction operation, guides the mobile mine as much as 13 kilometers each year along a 100-kilometer swath. Understanding where to go next demands a special kind of map.

Eramet operators choose the mine’s route, negotiating a path around or through farms and forests, using maps from an enterprise geographic information system (GIS). The technology helps make decisions across the mineral sands operation—and across the company.

“With this GIS platform all the data is shared, and we can anticipate every impact to manage,” said Davin Beukes, Chief Technical Officer at Eramet’s Senegalese subsidiary, Grande Côte Operations (GCO).

Eramet applies circular systems thinking with the goal to be not just sustainable but regenerative — extracting minerals and restoring land and livelihoods. As the mine moves, GCO staff consult GIS maps as they meet with local people and work to clear vegetation, build roads, install electricity infrastructure and replant the land. GIS shows where each of these activities must take place and helps different teams coordinate the sequence of the work.

“Now, we have 50 eyes watching the same thing every day,” Beukes said. “We understand each other’s pain points and collaborate better.”

Contributing lasting improvements for land and people

Inspired by the Paris Climate Agreement, Eramet changed many aspects of its operations. The company sold its smelting business and targeted the minerals that fuel the clean energy transition.

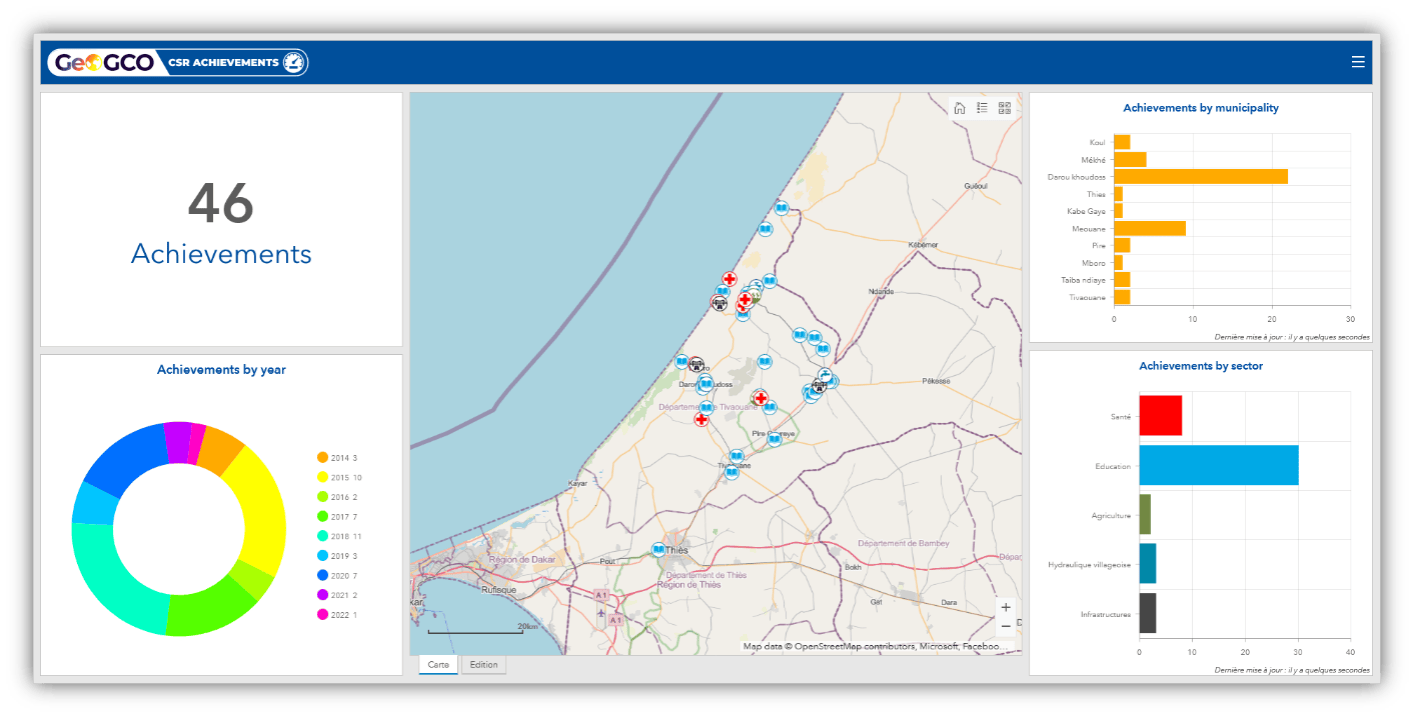

The company is in the process of implementing an environmental management system built with GIS technology at every mine to measure water, air and soil quality and to guide the company’s pledge to reach zero carbon emissions by 2050. The company has made many pledges to protect the lives of the people, economies and environments around its mines [see sidebar].

To monitor progress, Eramet must closely measure conditions and report its findings transparently. The company uses GIS to collect and integrate environmental measurements and operational data across the mining lifecycle — from exploration to operations to rehabilitation — and then display that data on maps and dashboards.

“We need a perfect understanding and knowledge of our impacts, positive and negative,” said Christine Deneriaz, environment director at Eramet. “GIS is a helpful and important tool for communication and operations. We need both a big-picture overview and precise data to know where we are.”

Outcomes for communities

Given the long path of the Senegal mine, many villages had to be relocated. GCO worked with the Senegalese government on this sensitive undertaking. Company operators collaborated with Senegal’s National Ecovillage Agency to resettle 25 families in 2016, and 85 families in 2019. The new villages include a mosque, health clinic and a primary school. A well and solar panels provide water and energy. For livelihoods, residents receive farmland, seed, fertilizer, irrigation water and an agronomist’s help to improve crop yields.

Communities were closely involved in defining how the resettlement process would take place. GIS helped GCO keep track of the sentiment of each landowner, and maps were used to convey the plans for the mine and the new villages.

Eramet has worked with families that refuse to leave their homes, some that only want to move temporarily, and others that are happy to resettle permanently. The company works to accommodate each perspective and reroute the mine if necessary.

“We’ve learned never to underestimate the power of communities if you are going to directly impact them,” Beukes said. The team works to gain permission, arrange compensation, and pursue community investment programs far in advance.

Restoring the Land

In 2023, the mineral sands mine in Senegal returned 80 rehabilitated hectares (nearly 200 acres) to the State of Senegal. GCO is the first mining company in Senegal to restore revegetated lands. The area of rehabilitated land will expand as the mine moves.

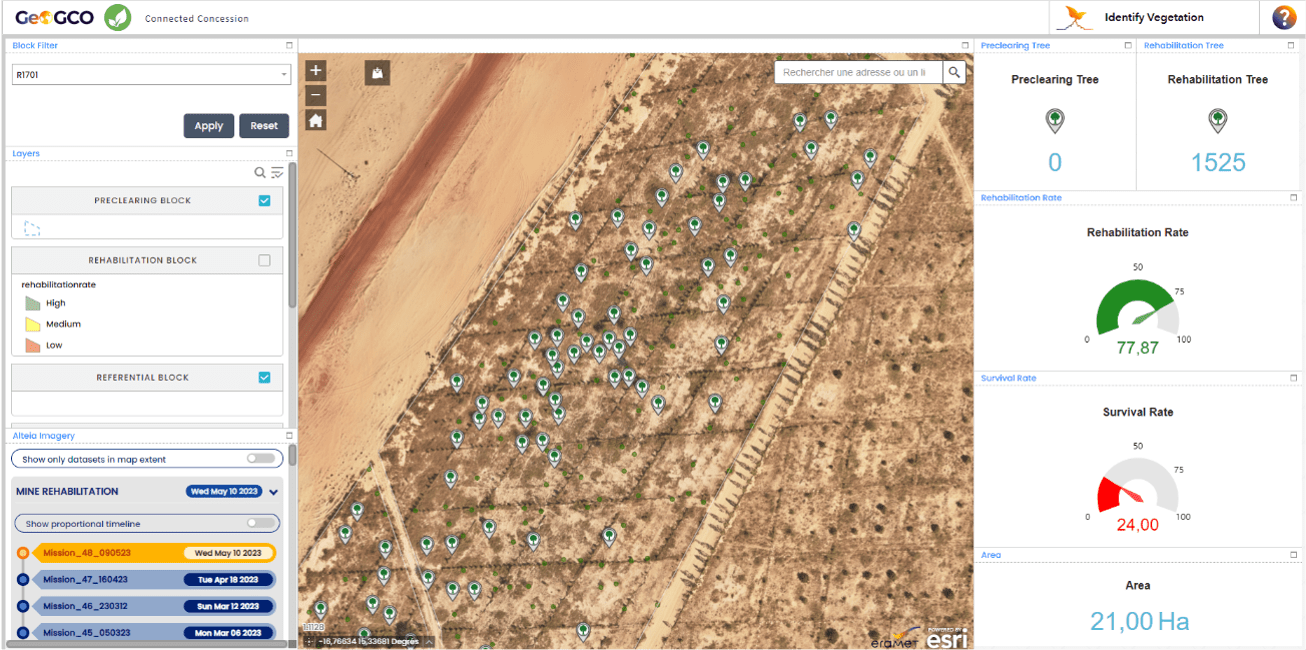

While some GCO staff plan the path forward, others focus on rehabilitating the land behind. GIS guides rehabilitation, allowing staff to map and analyze imagery collected from drone flights. They can identify areas in need of planting and conduct health assessments of areas recently planted. “We can see not only what we’ve planted, but how it’s growing,” Beukes said.

The drone improves safety by eliminating the need for personnel to go into dangerous areas to collect information. Drone data feeds a dashboard that displays metrics about rehabilitated land.

“Rehabilitation requires a long-term perspective,” Deneriaz said. “After we plant the trees, we may need 10 years before we have a productive and effective ecosystem.”

Operators of the mine appreciate how GIS lets them look across space and time to answer questions about mine progress. “It’s quite easy to show what we have mined and what we have rehabilitated,” Beukes said.

Reengineering how Eramet operates

GCO is pioneering a new approach in Senegal, targeting low-grade sands that don’t have as many minerals but avoid the problem of toxic slime biproducts that must be held in containment ponds. Without slimes, the mine can move quickly to make the low yields economically sustainable and have less of an impact on the land. The mining machine has an onboard water processing plant that cycles through the sand and filters out contaminants in the water. This intricate process is indicative of the transformation at Eramet to be a cleaner, more socially responsible company.

In the company’s shift to a clean energy focus, technology has played a greater role than before. Carine Stolz, information systems product line manager of Geology and Mining Services at Eramet, is in charge of GIS and other systems. Stolz and her team create GIS-powered applications to support business lines and connect to other enterprise systems that report safety, environmental incidents and more.

“We try to connect all the tools so the data can be pushed automatically to the map, and so there is no need to do the same job twice,” Stolz said.

It has taken Eramet six years to reposition itself as a sustainable mining and clean energy player, and Stolz feels the GIS apps her team has created help visualize the change and keep an eye on environmental and social impacts.

In Senegal, for example, the team developed a water quality monitoring system that has since been applied to Gabon with plans to deploy it elsewhere. It delivers water quality data in a dashboard to show thresholds and parameters important for environmental compliance.

The work to shift focus and retool at Eramet has started to pay off. “The transformation is really huge, with 50 percent of the company’s revenue set to come from the energy transition within five years,” Stolz said. “Information technology is one of the key motors of this transformation.”

Watch the video below to learn more about GCO's mine monitoring program in Senegal and read more about how GIS is used to digitally transform natural resources management for greater sustainability.